I’m a little late to the Voxel engine party, and it may not be the “cool” thing to do anymore, but it’s definitely an interesting topic, so perhaps there is still some buzz floating around. I’ve been playing around with procedural mesh generation in Unity3D and thought I’d have a go at building a little Voxel “engine.” I will make references to MineCraft (how could I not?), but consider claims relative to C#, Mono, and Unity3D; not Java.

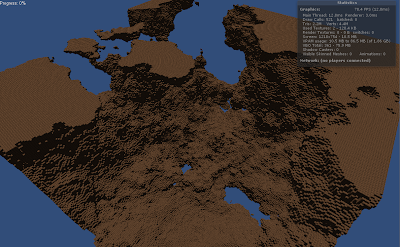

During the initial world generation sandbox phase. 2.1 million dynamically generated triangles running at 80 fps. A testament to Unity’s ability to make it rain.

Chunk It Up

When generating procedural environments or “worlds,” I found one of the major issues to be temporary object creation. I’m not talking about wasteful code or unnecessary data copying; I’m talking about data that is absolutely required to generate the environment. For example, in a game like Minecraft, the world is generated as the player’s position moves towards a location they have not traveled before. This data is then encoded and stored on the local disk. Should the player leave and return to that particular part in the world, the data would be loaded from disk instead of generated. Regardless of how the data is provided (generated or loaded), we can be sure that:

- The amount of data per “chunk” is identical once it reaches application memory

- There are many more “chunks.” Meaning, more memory is required.

The process from generated/loaded “chunk data” to a rendered mesh in the environment involves the creation of locally scoped storage, copying, and potentially, many different threads containing their own stack and added overhead. As this data is pulled through the render pipeline, it’s organized into data structures which, optimally yield the most efficient access. Most of the time, this means there’s at least one occurrence of added overhead. It’s up to the developer to determine whether or not that overhead is worth the gain from using such a data structure. That is the game you play when building this sort of application (most applications, really!), and this post is about my first struggle with finding that balance.

Thread it to Death

Sure of myself, my first approach to generating/building the environment was to create a pool of consumer threads and a pool of producer threads, and use a blocking priority queue for flow control. The producers would generate segments of the world as fast as they could and queue the chunk data in the priority queue (prioritized on the chunk position relative to the player position). If a consumer thread was available, it would grab the data and generate all of the geometry needed to create the Mesh. Once the consumer had generated the geometry for the mesh, it would dump that data back into a “special” queue where the main thread could dequeue the geometry and generate the mesh.

Sounds fast huh? Yeah, I wouldn’t know… I received a heap error after a few seconds of execution.

Too Many Heap Sections

WAT? I suppose it’s better than “Unknown Error”

I spent a lot of time tweaking the thread counts, re-using previously allocated memory, switching a few classes to structs to reduce heap usage, and I could not figure out why the application was dying. I read a Unity forum post concerning the error I was experiencing, and all I could really conclude is that I was creating and storing too many things at once. Perhaps “small arrays?”

Garbage Man

Of course, after years of being bitten in the ass by nagging concurrency issues, I started there. Low and behold, switching to a single background thread would avoid the horrible heap error, but the performance was miserable. On the bright side, at least, at that point, I could fire up the Unity Profiler, and see that the state of the garbage collector was constantly in “Oh Shit” mode. The problem was right in front of my face the entire time, and it was the simplest phase of the entire pipeline: Geometry -> Mesh

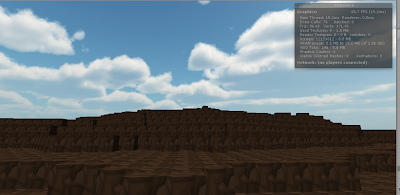

Screenshot when I thought I was at 60 fps, but moments later, it took a nose dive.

Thinking back to my first approach, having each Thread generate a part of the world isn’t really an over-the-top use of concurrency. It’s not like I was creating hundreds of threads. I was simply using a pool of 3-4 consumer threads and that’s it! Even after I switched to using single background thread, the garbage collector was still sucking wind! Why?

For the record, using a multi-threaded generation approach is problematic for other reasons as well. Specifically, when attempting to correctly implement an on-the-fly occlusion culling algorithm by comparing data in neighboring chunks. That’s an entirely different topic, but worth noting here.

Geometry isn’t Trash

Geometry generation from chunk data, explained simply:

- Figure out which faces aren’t completely surrounded by other faces.

- Add the face vertices, normals, UVs, and triangles (ordered vertex indices) for that face to the respective buffers.

- Create new Mesh instance and set vertices, normals, and UVs to the data in the buffer.

Because the size of the buffer is unknown, I decided to use a List<Vector3> for the vertices, a List<Vector3> for the normals, a List<Vector2> for the UVs, and a List<int> for the triangles. The class looked like this:

public class ChunkMesh {

private List<Vector3> _vertices = new List<Vector3>();

private List<Vector2> _uvs = new List<Vector2>();

private List<Vector3> _normals = new List<Vector3>();

private List<int> _triangles = new List<int>();

private int _triangleCount = 0;

public ChunkMesh() {

}

public void AddFaceFor(Block block, Vector3 normal) {

Vector3 worldPosition = (Vector3) block.World;

// Retrieve a generic quad definition given the normal

Quad quad = Quads.ForNormal(normal);

// Move the generic quad vertices to their world position

foreach (Vector3 v in quad.Vertices) {

_vertices.Add(worldPosition + v);

}

// Add all the UVs

_uvs.AddRange(quad.UVs);

// Add the normal for each vertex

int normals = 4;

while (normals-- > 0) {

_normals.Add(quad.Normal);

}

// Add the vertex indices that make up the quad

_triangles.Add(_triangleCount);

_triangles.Add(_triangleCount + 1);

_triangles.Add(_triangleCount + 2);

_triangles.Add(_triangleCount + 2);

_triangles.Add(_triangleCount + 1);

_triangles.Add(_triangleCount + 3);

_triangleCount += 4;

}

public Mesh ToMesh() {

Mesh m = new Mesh();

m.vertices = _vertices.ToArray();

m.uv = _uvs.ToArray();

m.normals = _normals.ToArray();

m.triangles = _triangles.ToArray();

return m;

}

}

After I’ve already lead into the problem a bit, you can see where this is going. At the core of the problem, I was creating one of these ChunkMesh classes for each Chunk, it collected all of the face data, then at Mesh generation, copies each data set into an array and dumps it on mesh. Once it’s on the Mesh, the ChunkMesh instace is no longer needed and is thrown away (awaiting garbage collection). The more you create, the more data has to be hauled to the dump, spread that same problem across multiple threads, and you’re in for a real nasty result.

Update: I failed to mention this, but the ToMesh() method was called in a MonoBehaviour.Update(), which was explicitly pointed out in the post on the Unity forums as being a big “no no.” That was the key to tracking down this issue in the first place.

Once the issue was resolved, Mesh generation was pleasantly speedy.

In closing, I’ve found that the best solution is to create a single buffer, limit it to the max vertices allowed for a single mesh (65536), and simply write the face data into the buffer, and copy it out, but retain the reference to that buffer so it can be reused. There is some light lifting involved with the buffering in terms of tracking the current vertex count and then using Array.Copy() to move the data around. The *big* tradeoff is that you shift the memory management responsibility to the Mesh cleanup, which Unity handles beautifully via the Destroy() method.

Using a single buffer also means that you’re limited to single thread access as well. Refusing to see the light, I did try creating a ThreadLocal implementation and experimented with different thread counts, and while this resulted in a successful world generation (no more heap error), it was really CPU intensive, and seemed to take away a bit from the Unity performance.

Unity has proven to be an extremely dependable platform for building games. Most of the issues I have encountered were instances where I was trying to solve a problem that Unity had already solved (and solved 100x better than I ever could). While there are certainly more than a handful of circumstances where multithreading can be used, a single background job and/or intelligent use of Coroutines are usually more than enough to achieve *incredible* performance for any style of game.